It's been said that the most dire threats are the ones that aren’t seen. And if some new data is correct, the U.S. mortgage market is about to be blindsided by a real doozy of a problem.

In December 2009, headlines were screaming in the financial markets that as many as 12 million mortgage homeowners in the U.S. were “underwater” — owing more on their mortgage than the house itself was worth, thanks to plunging home prices.

These borrowers came to be known as zombies, or the walking dead. It was the threat everyone saw coming.

Yet, sticking by that zombie analogy, many of the previously dead have since been reanimated as home prices recovered. In 2013, for example, U.S. home prices rose 11.3% according to the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices.

In many ways, we’ve come a long way from December 2009 — and although underwater mortgages remain a problem at nearly 6.5 million homes, or 13.3% of all residential properties with a mortgage according to CoreLogic data in February 2014, it’s a problem that has been decreasing steadily.

THE THREAT THAT ISN’T SEEN, YET

Negative equity lock-in represents the threat that’s been in plain view for years now. But it’s what the market doesn’t yet see coming that’s the real problem.

That threat? So called “rate lock-in effects,” according to researchers at the Institute for Housing Studies and DePaul University, who studied the effect using in-depth housing data for Cook County, Chicago.

“Interest rate lock-in occurs when a household has a nonassumable, or non-transferable, mortgage with a low interest rate and rates then rise,” the DePaul researchers noted.

As refinancing activity wanes and the U.S. mortgage market shifts to a more traditional purchase market, move-up buyers typically tend to comprise at least half — if not more — of that market.

But that doesn’t seem as likely to happen this time around, because a vast majority of existing homeowners who had the ability already refinanced their mortgages during the recent refi wave.

From 2009 to 2012, in fact, almost 22 million borrowers refinanced their existing mortgages, according to HMDA data. And that has direct implications for the sustainability of purchase mortgage volumes moving ahead.

Rates are indeed rising now, grinding higher in 2014 and likely into 2015, as the Federal Reserve continues to back off of its support of the mortgage market. After reaching 3.4% in the middle of last year, the 30-year Freddie Mac Primary Mortgage Market Survey shows rates now hovering around 4.4% in early 2014.

The refi boom has run its course, and while recovering home prices lift more and more households out of negative equity lock-ins, rising mortgage rates combined with historic refinancing volumes in recent years mean many more households are being pushed into a scenario of interest rate lock-in.

And here’s the thing: we’ve seen all of this before. Let’s rewind the tape a few decades. Like most things in life, a mortgage market constrained by rising rates isn’t a new thing.

In fact, severe interest rate lock-in affecting borrowers en masse was last seen in the late 1970s and into the 1980s — during the great inflation battles that set the stage for the Reagan era. Back then, rates on 30-year fixed mortgages rose from 10.1% to 17.8%, according to Freddie Mac data.

Research focused on this time period found that household mobility dropped 15% for each 2% increase in mortgage rates. That’s a sobering statistic to consider as we head toward another rate lock-in period for the mortgage industry, and a mortgage rate picture that could be anywhere between increasing and wildly increasing.

TIME TO SOBER UP, AND QUICKLY

The DePaul University researchers discovered something far more sobering, however, than the previous research from the 1980s-era rate lock-in. In particular: the effects of interest rate lock-in are far more significant than the effects of negative equity lock-in.

After controlling for a host of demographic and economic factors, the researchers at DePaul University found that a 10% jump in households burdened by negative equity lock-in decreased housing turnover by 13% (which makes sense, as we clearly saw that previous fears of strategic default by underwater homeowners were overblown.)

But a similar 10% jump in interest rate lock-in among households? The result was a far more dramatic 29% drop in housing turnover.

Beyond the much broader (and significant) economic and policy effects of decreased labor mobility — constrained economic growth, driving a negative feedback loop to mortgage lending over time — the more direct implication of this research is that the emerging purchase market for mortgages likely won’t see much involvement from move-up buyers any time soon.

Here’s why: according to U.S. census data for the most recent period, roughly 50 million homes had an existing mortgage of some sort in 2009. With 22 million borrowers refinancing, that’s nearly half of the entire viable market of would-be move-up buyers facing interest rate lock-in.

And in truth, it’s likely more than that, since most move-up buyers are typically higher earners. According to the DePaul University researchers in analyzing Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data, nearly half of the 22 million that refinanced during the most recent refinancing wave made 120% or more of their area’s median income, and 44% lived in higher-income neighborhoods.

RISING PRICES WON’T BE ENOUGH

Astute observers might already be asking: well, sure, rates are rising — but so are home prices. And one can offset the other, right?

If this is you, you might want to make sure you’re sitting down.

The DePaul University researchers found that households finding themselves “unlocked” from negative equity positions by rising house prices likely wouldn’t be sufficient to offset an increasing number of households locked in by steady rate increases.

Read that again. Rising rates will swamp households faster than rising home prices can save others.

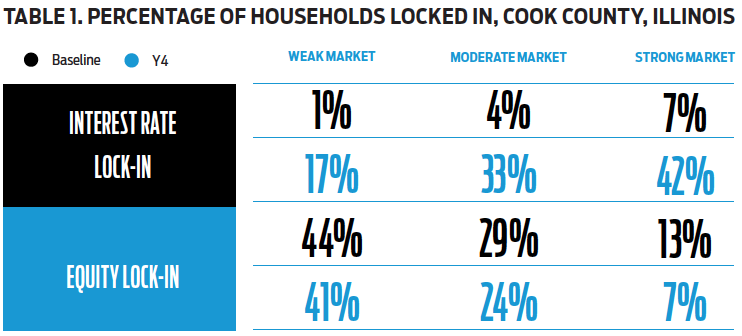

The researchers ran a simulation that took 2011 market conditions as the baseline; then increased home prices by 10% in year one, projecting how lock-in effects would change based on a series of annual one percentage point increases in mortgage rates through four years.

The results of the simulation clearly show the reverse side of the negative equity problem: whereas 44% of households in weaker housing markets among the DePaul University study were locked-in by negative equity in year one; only 13% of households in stronger markets were similarly affected.

Interest rate lock-ins are the flip side to this problem. In the DePaul study, while 17% of households in weaker markets found themselves locked-in by mortgage rates after four years, a whopping 42% of households in the strongest housing markets found themselves stuck by rising rates.

Source: Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

“The number of households ‘unlocked’ by the modest price increase are far less than the number of households locked-in by the rising interest rates,” the DePaul researchers noted in their conclusion.

That’s startling enough. But it’s the rest of their conclusion that bears strong attention:

“The result would be a dramatic slowdown in housing turnover. The slowdown would be most pronounced in the strongest housing markets where households were more able to take advantage of historically low interest rates to refinance their mortgages.

“In Cook County, as is occurring nationally, the strongest housing markets have been leading the housing market recovery. The findings raise concerns that significant increases in long-term interest rates could reduce housing turnover rates in these areas, slowing an overall housing market recovery and threatening broader economic gains.”

To put this into context: this is both a mortgage issue and a major economic issue — and it’s one that we’re not yet paying enough attention to. It’s a mortgage issue because the industry is depending on a more stable purchase market to emerge, and soon. This research suggests that a more stable market might be a mirage with a potentially moribund market for move-up buyers, placing far more emphasis on first-time buyers to drive purchase demand in the future.

Most of the first-time buyer segment will be in Generation Y — a generation that by most estimates has yet to see sufficient income growth to make a home purchase a reality, to say nothing of stringent underwriting criteria keeping many first-time buyers on the sidelines.

But this issue goes well beyond mortgages, too: a substantial drop in household mobility would have strong negative effects on economic growth, according to most published research on the subject — and in fact, may be one reason that economic growth thus far has been short of expectations.

The DePaul University research suggests that mortgages are about to become an even greater drag on prospects for economic growth, especially as the Fed continues to dial back its quantitative easing asset purchases and rates naturally rise.

From a policy perspective, perhaps the best option isn’t to attempt to unlock borrowers who refinanced into historically low interest rates: it’s to determine how to best drive forward demand by offering loan products that allow first-time buyers into the market; help previously-distressed homeowners obtain access to credit; and allow equity unlocked borrowers to more easily move up for those that can.

Interested in reading the full DePaul University paper? CLICK HERE.