#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;}

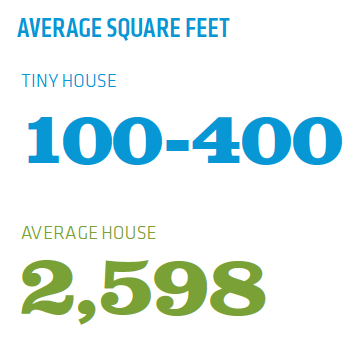

Tiny homes get a lot of press these days, from HGTV marathons to Millennial blog posts, and for good reason. The trend combines minimalism with green living and debt-free housing — a pretty powerful combination. It is also endlessly watchable, as seeing people squeeze into tiny homes that are often less than 200 square feet is weirdly cathartic in a world where the average new build in American is more than 12 times that space.

But for those in the housing industry, the question is: How do you make any money from tiny homes? We set out to find the answer, and came up with these two avenues to tiny house treasure.

FINANCING

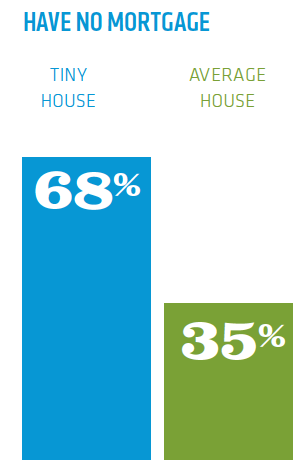

Financial freedom is a central tenet of the tiny house movement, so a mortgage would seem counterintuitive for the buyers and, at the low price point of most tiny houses, unappealing for lenders. In addition, just like manufactured homes, some tiny homes might not be eligible for mortgages because they don’t own the land they sit on.

But a mortgage isn’t the only way lenders can assist would-be buyers. One alternative is to structure RV loans for tiny homes, since some are built on trailers and come with a requisite vehicle identification number. A number of tiny home manufacturers are now building according to these specifications.

Others, however, are wary of how the RV designation fits the tiny house model.

According to the Recreation Vehicle Industry Association, which grants RVIA certification to manufacturers, a recreational vehicle is “a vehicle designed as temporary living quarters for recreational camping, travel or seasonal use. RVs may have their own motor power (as is the case of motorhomes); may be mounted (as are truck campers); or towed by another vehicle (as are travel trailers and folding camping trailers). Not included in the RV definition are conversion vehicles, off-road vehicles and manufactured housing for long-term residences (manufactured and modular housing).”

The meaning of “long term” in that definition is pretty nebulous. Does long term mean a month, a year, or five years? Don’t some recreational vehicle owners live in their vehicles on an ongoing basis? And does anyone really regulate this requirement?

Within this uncertainty, some lenders see opportunity. RockSolid Funding, based in Colleyville, Texas, funds several kinds of recreational use vehicles, including non-motorized RVs (read: tiny homes), for both dealers and borrowers. RockSolid requires two years of prior established installment history and some debt-to-income requirements for borrowers. Rates can range anywhere from 5% to 19.95% and the terms, which depend on credit history and loan amount, range from 12 months to 15 years.

Another way to fund tiny homes is through unsecured personal loans. The number of lenders in this space has multiplied in the last few years, and now includes LendingClub, CircleBack Lending, Springleaf, Prosper, SoFi and Lightstream. Because the underwriting of these loans is based on the credit-worthiness of the buyer, borrowers are free to use the funds for whatever purpose they like, including tiny homes.

While most of these lenders fund loans up to $35,000, SoFi and Lightstream will loan up to $100,000, which is not an unusual price tag for a tiny home.

Todd Nelson, Lightstream’s business development officer, says he has seen some bare-bones tiny home building kits in the $20,000 to $30,000 range, but also many nicely equipped tiny homes where buyers borrowed $75,000 to $80,000. Tiny homes with all the bells and whistles can easily come in at $100,000, and many buyers borrow not just the tiny home price, but enough for land or needed upgrades, like a solar array.

“One of the challenges for borrowers is that these homes, especially in the upper range, are a big-ticket purchase for them, but the loans aren’t particularly attractive to lenders,” Nelson said. “Lightstream offers a flexible product, whether it’s for a portion of the tiny home or a whole project.”

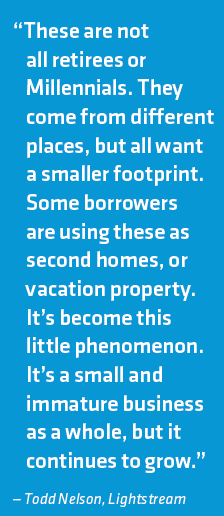

Nelson said Lightstream has seen an uptick in people borrowing to fund tiny homes.

“These are not all retirees or Millennials. They come from different places, but all want a smaller footprint. Some borrowers are using these as second homes, or vacation property,” Nelson said. “It’s become this little phenomenon. It’s a small and immature business as a whole, but it continues to grow.”

Lightstream is an online division of SunTrust Bank, and Nelson said the lender sees a long-term value in providing these loans. “If these are Millennial buyers, they may not be ready for a traditional home loan, but this is their first entry into the marketplace and homeownership. When they need a bigger space, this loan is a good step into a mortgage.”

Is the company’s strategy paying off? In the first quarter of 2016 SunTrust reported that, “compared to the first quarter of 2015, growth was concentrated in C&I loans, nonguaranteed residential mortgages, consumer direct loans, and commercial construction loans.” It’s hard to tell what kind of impact tiny homes had in that mix, but at least they were part of the growth sector for the company.

#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;}

BUILDERS/DEVELOPERS

The tiny home movement is rooted in green living and for many proponents the small house is just part of a larger desire to live “off the grid.” But as the movement grows, the isolation and hardship of living off the grid — or in someone’s backyard — has become less appealing.

The number of stories about tiny house dwellers giving up the lifestyle after a short time are growing, but have a common theme — it’s the isolation from people and resources like grocery stores that are the problem, not necessarily the small space.

In 2015, Tech Insider profiled five people who abandoned tiny homes, including Jonathan Bellows, a 30-year old who built a 130-foot home outside of Flint, Michigan. “I thought that being out in the country was what I wanted. I figured I would have my own land, have my own property, be my own master, but I came to find out that it’s very isolating. I felt very alone,” Bellows said in the article.

Bellows also ran afoul of local zoning laws, which made it illegal to build a house under 960 square feet. These types of zoning requirements are a common obstacle for tiny homeowners, but present a real opportunity for real estate developers.

Bellows also ran afoul of local zoning laws, which made it illegal to build a house under 960 square feet. These types of zoning requirements are a common obstacle for tiny homeowners, but present a real opportunity for real estate developers.

Lloyd Alter, writing at treehugger.com, says, “In fact, the only way the tiny house movement is going to succeed is if people get together and build intentional communities of tiny houses, which will solve the land, loans and laws problem and eliminate the fear and social pressures ones.”

It’s a common-sense approach that could broaden the number of people living in tiny homes, especially in cities. As Alter notes, “Lots of people all over the world live in tiny houses; they are called apartments.”

Until recently, the few dozen tiny communities across the country were run largely by proponents of tiny living who had banded together or as affordable housing for the homeless.

But that all started to change in 2014, when creating tiny house communities started gaining momentum among some traditional builders who want to have a stake in the new trend. Bryan Smith Homes, a luxury homebuilder in the Dallas Fort Worth area since 1977, opened Texas Tiny Homes in 2012 and applies the same custom approach to tiny homes as it does to traditional homes.

For one thing, the company doesn’t build homes on trailers. As stated on the company’s website, “The difference between our homes and all the tiny homes on trailers is in 30 years, every one of our homes should be worth more than you paid for them, the tiny homes on trailers will be worth very little, if anything. Same is true with your $75,000 Escalade SUV or $50,000 BMW.”

The company sells tiny home plans but also specializes in custom tiny builds. Its smallest, least expensive home starts at a base price of $65,000, which does not include land, a septic system or other items like solar systems or driveways. As a land developer, Texas Tiny Homes is working on a community of tiny homes and hopes to have lots available for purchase in Texas in the near future.

In fact, building tiny house communities is one of the company’s primary goals. “Part of the vision we had for launching Texas Tiny Homes is to provide investment opportunities for retiring Baby Boomers who would like to own and operate their own village of rental properties, in resort locations of their choosing,” the company states on its website.

Texas Tiny Homes will help locate land, site-plan it, process any city council zoning requirements by local municipalities and bid the project out to local utility and paving contractors.

Sprout Tiny Homes, a certified manufacturer of tiny homes in Colorado, is breaking ground on two residential communities, one in Salida, Colorado, near the Monarch Mountain ski area and one in Walsenburg, Colorado, a historic mining town. The development in Salida will feature 200 tiny homes, a community building with catering kitchen, exercise facility and management office and 96 storage units.

Walsenburg’s new marijuana grow operation is expected to create up to 400 new jobs in the area in the near future, but housing is hard to come by. So Walsenburg adopted a zoning ordinance that is friendly to tiny homes, and Sprout is planning 33 units within walking distance to downtown and several new businesses, including the grow plant. That business has already expressed interest in renting out the homes for employees.

In Sonoma, California, Jay Shafer, a tiny house champion who founded Tumbleweed Tiny Homes and Four Lights Houses, is developing a tiny house community that overlooks a wildlife habitat but is still walking distance from amenities like a grocery store and café. According to tinyhometour.com, Shafer hopes to have it completed by the end of this year.

The community in the swanky Sonoma County is zoned as an RV park, so all of the tiny houses will be built on trailers. This designation allows the community to skirt minimum square footage rules, but deprives the city of property taxes. However, the city has been on board since the beginning, according to the website, since the community was designed as an urban infill and provides much-needed housing in a very expensive area.

The community will look very different from a traditional trailer park, with the tiny homes designed like old-world cottages in a park setting. The project has already expanded from its original footprint to include 60 tiny homes, all from 100 to 400 square feet.

The community will include a 2,300-square-foot common house, a community workshop, bike parking, 12 small guest rooms and a shared kitchen and bathroom. Each house will also have a 50-square-foot storage shed.

Whether tiny homes take the country by storm or prove to be a short-term fad remains to be seen. And the scale of profitability with either financing or developing tiny homes is minuscule compared to the overall housing market. But one thing is certain. In solving fundamental housing problems of space and affordability, the tiny house movement is worth watching and maybe even learning from.