In early August, President Obama reminded lawmakers of their consensus to wind down Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

He was talking before a gathering in the apt surroundings of Phoenix. The choice of location — at a construction company no less — was clearly no accident. The Arizona desert city was a poster child for the housing crash that enveloped the U.S. in 2008. These days, the president said, the Phoenix metro area is experiencing one of the nation’s most rapid housing recoveries.

“A reformed system must have a limited government role, encourage a return of private capital, and put the risk and rewards associated with mortgage lending in the hands of private actors, not the taxpayers,” the White House said in a fact sheet released to the press.

The call for government-sponsored enterprise reform finally came from the top. But will anyone listen?

The president provided much-needed momentum for a mortgage finance overhaul, but as the saying goes, “Easier said than done.” GSE reform is simply much easier to talk about than to do.

It’s been five years since behemoths Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were placed into conservatorship as the government agonized whether their precarious conditions would put a financial system already in crisis into a tailspin. Who knew that five years later, we’d still be talking about what to do with them?

Reforming the GSEs is a monumental task with far-reaching implications that will affect housing affordability and sustainability for future generations. Big questions must be answered: How big should government’s role be in housing? How do we protect the taxpayer? Is plenty of private capital available? How important is the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage?

There have been plenty of proposals over the past five years. Right now, a handful of them have Washington animated about GSE reform, and mortgage industry insiders, policy wonks and politicians are expressing tempered optimism that advancements will be made this fall and into next year.

“There is a lot of interest, and things are moving forward,” said Phillip Swagel, who served as assistant secretary for economic policy at the Treasury Department from 2006 to 2009 under President George W. Bush.

“We’ve seen it already with FHA reform. Senators (Tim) Johnson and (Mike) Crapo very quickly reached a bipartisan agreement on FHA reform, and I think a lot of people thought — including me — that it would take much of the fall,” said Swagel, now a professor at the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland.

GSE reform requires patience. Nobody suggests a bill will hit President Obama’s desk before year-end, but some feel confident a bill could reach him next year. Still, plenty exists to distract lawmakers: Syria, budget talks, immigration reform, the debt ceiling and approaching midterm elections.

Gaining momentum

Still, momentum is building via a bipartisan bill put forth by Senators Bob Corker, R-Tenn., and Mark Warner, D-Va., that would provide a government guarantee.

As HousingWire went to a press, Senate Banking Committee Chairman Tim Johnson, D-S.D., and ranking member Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, were busy holding meetings with stakeholders in the possibility of either introducing a new bill or amending Corker-Warner. Either way, Corker-Warner legislation at this point has been used as the template to move the process forward through the Senate Banking Committee. Hearings were under way during the fall as the process progressed. The goal, said Capitol insiders, is a markup of a GSE reform bill by the Senate Banking Committee by year-end.

Over in the House, U.S. Rep. Jeb Hensarling, R-Texas, wants nothing to do with a government guarantee on mortgage-backed securities. The conservative Texas lawmaker wants a fully private market. Like Corker-Warner, his bill would wind down the GSEs in five years. It also relaxes and eliminates some requirements under the Dodd-Frank Act.

Sense of urgency

There needs to be a sense of urgency to get GSE reform done, said Julia Gordon. Gordon is the director of housing finance and policy at the Center for American Progress.

although the housing market is recovering, it isn’t where it needs to be to provide for a robust, sustainable and accessible market, Gordon said. To illustrate her point, Gordon notes that roughly two-thirds of originations in the second quarter were for refinances, not purchase mortgages; that the percentage of homeowners has declined nearly 5% since the crisis, and that young buyers, first-time homebuyers and persons of color have largely been shut out of the market since 2008.

“Access to credit remains very tight. It remains tight not just because of the crisis or because of new regulations but also because of the uncertainty in capital markets about the future of the government guarantee,” she said. “Until that uncertainty is resolved we will not see the kind of investor interest we need to support the deep and vibrant market we want to have,” Gordon said.

Politically, Federal Housing Finance Agency Acting Director Ed DeMarco has moved the GSEs over the past five years toward a system that resembles a purely private system — a direction that doesn’t jive with the Obama administration’s housing goals. It’s a conflict that will need to be resolved as GSE reform moves forward, Gordon said.

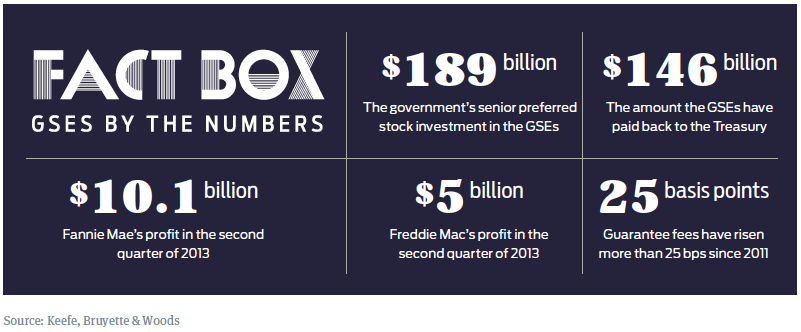

Any lack of resolve now could make it even harder to wind down the GSEs later. That’s because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are raking in money again. Expect more interest from congressional committees that deal with budgets and finance. And on Capitol Hill, more committee involvement will certainly slow the reform process, especially if Fannie and Freddie get factored into the annual budgeting process.

In fact, there exists a “Keep the GSEs” contingent that isn’t ready to throw out Fannie or Freddie although, at this point in time, their voices are muted compared to those supporting a new system.

There are certainly benefits from the functions of the GSEs, said Janneke Ratcliffe, executive director of the Center for Community Capital at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who isn’t advocating keeping Fannie and Freddie, but said she understands the argument.

“The ‘Keep the GSEs’ discussion is beginning to sort out and clarify some of those details,” Ratcliffe said. “There are important things that the (current) structure provides. Now the question becomes, ‘Do you have to go with what you’ve got to achieve those functions or is there a better way than simply keeping the GSEs?”

If the new model is so uncertain or unclear for various constituencies — whether it’s affordable housing groups or small mortgage players who seek a level playing field — then there is appeal to keeping “the devil you know,” Ratcliffe said.

Few would argue that keeping things exactly as they are, with the GSEs under conservatorship and the government sweeping up their profits each quarter is a good idea over the long-term.

Certainly, a handful of hedge funds want to keep Fannie and Freddie around because of junior preferred shares. If the GSEs were to completely repay the government and continue operating, these hedge funds hope for eventual payment of dividends on preferred shares that are not held by the government. Several funds that hold junior preferreds recently sued the U.S. Treasury over this issue.

Still, most of Capitol Hill appears to have bought into the idea that Fannie and Freddie should go.

Corker-Warner

The most talked about bill is the bipartisan Corker-Warner bill. Many believe this bill — the Housing Finance Reform and Taxpayer Protection Act of 2013 — will move the debate forward and could form the basis for eventual reform that makes it all the way to the president’s desk. Although Corker-Warner may not move through the Senate Banking Committee in its current form, it is expected to inform a bill now being worked on by Johnson and Crapo.

The Corker-Warner bill would create a government agency, the Federal Mortgage Insurance Corp., or FMIC for short, that manages a shared-risk insurance fund that is paid for via a strip on every security covered by the guarantee. It would monitor market players who would issue securities that are covered by the government backstop.

Sharing risk is a key tenant of the bill, which specifies that a private risk-sharer must take up to 10% of the first losses on any securitized pool of mortgages.

The bill winds down Fannie and Freddie over a five-year period, although, realistically industry and policy experts expect it to take longer, perhaps as long as a decade for the complete wind down.

“Political consensus on the appropriate role of government in the mortgage market has been difficult to reach, with many Republicans opposing any permanent support for the GSEs, and many Democrats opposing a system that lacks a federal backstop,” said Alec Phillips in a Goldman Sachs research note. “The Corker-Warner proposal bridges this gap, but establishing a backstop only after private capital has absorbed very large losses.”

Beside the 10% first loss private capital buffer it would also require a separate federal capital buffer of 2.5%, also funded out of mortgage guarantee fees. It’s a capital level thatis more than three times the overall mortgage losses experienced by the GSEs since 2007.

David Stevens, president of the Mortgage Bankers Association, said the industry believes strongly in an explicit and broad government guarantee and doesn’t think a more narrow, catastrophe guarantee will work.

“A catastrophe insurance structure suggests private capital is lending all the money and only in event of complete failure does the government step in,” he said. Such a model doesn’t ensure the 30-year, fixed-rate TBA market or ensure liquidity in a poor economy.

“The MBA’s position is first and foremost that private capital should not be crowded out of the market. We also recognize that we need continuous liquidity in all markets, good and bad. In order to do that, that will require some form of an explicit government-backed guarantee on a mortgage-backed security,” he said. “You can’t just invent that overnight when markets contract in the next recession. It has to be functioning in good markets and bad,” Stevens said.

The MBA also wants to ensure continuous access to the 30-year fixed-rate TBA market, which it doesn’t believe would exist in a fully private mortgage finance market. And like Corker-Warner, it wants significant first-loss provided by private capital. Under the current GSE structure, credit enhancement is only required for LTVs greater than 80%. That still leaves the taxpayer at risk if there is significant home price depreciation plus a foreclosure. The MBA doesn’t want the government guarantee tapped so easily and believes reform can be structured so that the government isn’t on the leading edge of loss.

“There are alternatives that can keep continuous liquidity but reduce the government’s risks significantly without pulling the legs of the stool out altogether,” Stevens said, “and having the entire housing system fall on its proverbial rear.”

Housing advocates want say

While Corker-Warner is written from a capital markets perspective, groups that represent homeowners want to make sure the final GSE reform bill includes consumer protections.

One of those groups is the newly formed grassroots group, America’s Homeowner Alliance. Phil Bracken, chairman and founder of the group, said GSE reform was a primary reason for launching the group.

Bracken is a former executive vice president of government and industry relations at Wells Fargo and former CEO of America’s Mortgage Co. He said homeowners need a voice in the debate as homeownership still remains the American Dream, even in the wake of the financial crisis.

“The desire for homeownership is as emboldened as it has ever been. The reason is people understand it is truly the only way to obtain generational wealth in America,” he said.

The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University forecasts the number of minority households will grow by 8.7 million over the next 10 years, accounting for seven out of 10 net new households in 2013–23. Although minorities account for a growing share of potential first-time homebuyers, they have few resources to draw on for a down payment, the JCHS report said. Among renters aged 25–34 in 2010, median net wealth was only $1,400 for blacks and $4,400 for Hispanics, compared with $6,500 for whites.

These homebuyers will need low-down payment and fixed-rate financing in order to become homeowners, Bracken said. GSE reform, he said, needs to be framed “to meet the needs” of America’s emerging homeowners.

The group will promote GSE reform that includes the fixed-rate 30-year mortgage, low down payment options and a well-capitalized and robust private market that includes an explicit government guarantee.

Finding a new path

Texas Congressman Jeb Hensarling, R-Texas, and Rep. Scott Garret, R-N.J., introduced the Protecting American Taxpayers and Homeowners Act, or PATH, over the summer. Hensarling’s bill phases out Fannie and Freddie within five years, reduces the role of the Federal Housing Administration, and relaxes some regulations under the Dodd-Frank Act. But it provides no government guarantee. Critics contend that would mean the end to the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage although Hensarling contends the 30- year can exist without a government guarantee.

The key challenge for Hensarling’s bill moving beyond the House is the lack of a government guarantee, said Mark Calabria, director of financial regulation studies at the Cato Institute. Calabria believes PATH will successfully pass in the House and make it into conference committee, but he said compromise must occur over the lack of guarantee for it to progress from there.

“By and large, all the Washington stakeholders want a guarantee that is there every day of the week,” Calabria said, even though he, like Hensarling, believes a guarantee isn’t needed.

“I think there is plenty of evidence that the private market can do this on its own,” Calabria said. “But if you are going to do a guarantee, it really seems to me that it should be catastrophic only.”

One thing to consider, however, is that with a catastrophic backstop, it would be difficult for a GSE reform bill to include affordable housing goals supported by a broad coalition of housing, mortgage and consumer groups. To establish a housing trust, for example, one would need a guarantee that is there all the time providing continuous cash flows to provide grants for affordable housing initiatives.

“A lot of the conversation has talked about a guarantee like it’s a light switch. I think it is better to think of the guarantee as a dial. How generous, how expansive is this guarantee?” Calabria said.

Although the MBA disagrees with PATH over the guarantee, it still believes the bill is thoughtful and workable if compromises can be made. The mortgage industry, for example, likes reductions in regulatory oversight and the common securitization platform found in the PATH Act.

Stakeholders in the matter will need to be calm and analytic — and make some concessions — to get to a final bipartisan bill that Congress will support.

“I don’t have an extreme view adversely about any of the bills,” said MBA’s Stevens. “I think they are all models that help us frame the debate. Once we really engage in the debate through the policymaking process, I think it’s going to force these bills to come together if we want to have a law,” he said.

“Compromise will have to be part of these final measures,” he said, “but I feel very optimistic that we’ll come up with a bill that is workable.”