#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;}

About a week before the November 2016 election, the U.S. Treasury market started to move lower. The cause of this increase in yield on the benchmark 10-year bond was not fear of an interest rate hike by the Federal Open Market Committee or the specter of higher inflation. No, the outlier event that shook the financial world out of years of torpor was a commercial real estate developer named Donald John Trump.

The move in the 10-year Treasury had a chilling effect on the mortgage business, which up through October had been having a very good year. Momentum and fat pipelines carried the industry through the rest of 2016 in good fashion, leaving the year up from 2015 at about $2 trillion in new mortgage originations.

For the first time in several years, the body of mortgage debt and thus servicing assets actually grew after years of watching the proverbial ice cube melt. But as 2017 began, the impact of higher interest rates on loan production and secondary market pricing was clearly negative.

Back in February 2017, the Mortgage Bankers Association projected a double-digit drop in mortgage originations, primarily based upon a sharper fall-off in mortgage refinancing transactions, despite a 10% uptick in purchase mortgages. Needless to say, with numbers like this in the industry’s collective face, widening the credit box has become topic A for loan originators and aggregators alike.

That said, the MBA numbers suggest a dramatic slowdown in loan prepayments with total mortgage debt climbing from 2016 through 2019 despite the slowdown in new production.

The volatile interest rate environment starting in Q4 2016 has impacted both lenders and issuers of MBS. The good news was that mortgage servicing rights (MSRs), those troublesome intangible assets that represent the right to collect a fee for servicing loans for others, rose in value at the end of 2016. The bad news is that many mortgage banks, including industry leader Wells Fargo, took a hit on their interest rate hedge in Q4.

The strong rebound in pricing for MSRs seen in Q4 2016 may not endure in 2017. A big factor in that analysis is the direction of the 10-year Treasury, which in turn governs mortgage originations. With the uptick in the 10-year bond yield after last October, estimates for mortgage refinancing volumes plummeted and guesstimates regarding loan prepayments likewise fell, thus increasing the net present value of the estimated cash flows from the MSR.

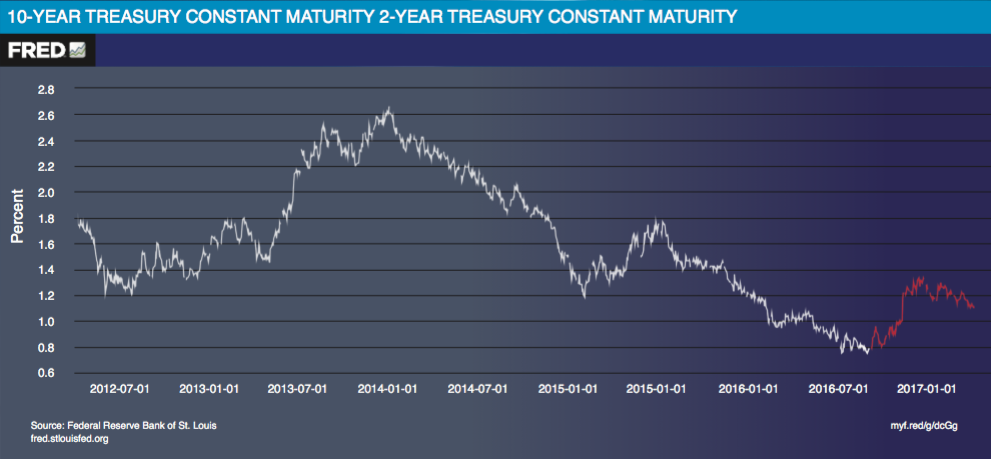

But if, as many investors expect, the 10-year bond rallies as 2017 unfolds, look for mortgage refinancing volumes to rebound and MSR pricing to fall as prepayment assumptions start to rise again. This is the roller coaster that the election of Donald Trump has delivered to the residential mortgage market. In addition, given that the Federal Open Market Committee has apparently decided to raise short-term interest rates several times this year, the industry could be facing the delightful prospect of a flat yield curve by the end of 2017 (click on chart below to enlarge).

#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;}

The Fed currently owns about $1.7 trillion in MBS and another $2 trillion in U.S. Treasury debt, a huge chunk of duration that has been removed from the financial markets and acts as a cap on long-term interest rates. The chart shows the spread relationship between the 10-year T-bond and the 2-year T-note, which is now tightening as long-term rates fall. Note the upward gap in the 10-2 spread around the time of the November election.

The combination of volatile interest rates and increased competition for loans has caused secondary market execution for many lenders and aggregators to deteriorate as 2016 came to a close. Top-10 aggregator Flagstar Bank, for example, managed to increase loan sales volumes, but saw its gain-on-sale margin fall to just 0.94% from 1.09% in 2015. The bank said in its 2016 10-K that “the increase was partially offset by lower loan sale margins driven by pricing competition.”

Flagstar’s chief operating officer, Lee Smith, said at the IMN Mortgage Servicing Rights Forum in March that the biggest issue for him with respect to the secondary market is what happens to the GSEs and Ginnie Mae:

“I think the No. 1 issue is how the agencies will evolve. What will they evolve into? And what happens after January 10, 2021, when the temporary rule allowing agency approved loans to remain as qualified mortgages (QM) despite debt-to-income ratios higher than 43%?

“Do these become non-QM and subject to the ability to repay (ATR) rule? This is probably a bigger deal for the government than conventional markets. Underwriting standards are pretty tight and if they tighten again, with home affordability nearing the lowest level in seven years, it would be bad news for the housing market.”

While there continues to be a lot of talk about reforming the GSEs or at least getting them out of government conservatorship, there is little appetite in Washington to disturb the status quo.

Indeed, a bipartisan group of senators recently told Federal Housing Finance Administration head Mel Watt that he shouldn’t allow the companies to recapitalize without congressional approval. The Treasury is currently “sweeping” all of the profits of the GSEs to compensate taxpayers for the $187 billion in preferred capital injected by the government after the 2008 financial crisis.

The difficulty with the GSEs, however, is that the manic swings in the bond markets, a secular decline in lending volumes and the competitive advantage of Ginnie Mae could see one or both agencies forced to seek additional funding from Treasury. In that event, the Republican-controlled Congress might indeed opt to push Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into receivership, which would have the advantage of zeroing out the private shareholders once and for all. Congress could then fashion reform legislation to find a new configuration for the GSEs.

Mark Freeman, treasurer of Ocwen, has a different set of issues when it comes to the secondary market, like many of his peers wondering when and how the common securitization platform for the GSEs will come to fruition. He also notes that in terms of lending, the GSEs seem to be ever-researching and tweaking expanded credit criteria, yet the originators (e.g. large banks) continue to be skeptical and their credit overlays “essentially wipe a lot of those products out.” He added that the FHA is “a continuing saga of originators not wanting to participate because of the buybacks and lawsuits.”

Perhaps the most troubling issue facing the secondary market in 2017 is the fragile condition of the nonbank sector, particularly the seller/servicers that operate in the government-guaranteed market.

Moody’s recently put out a report predicting that financial pressures would drive consolidation in the nonbank sector, something that has been discussed for years. The fact that commercial banks have been retreating from the residential market and especially the Ginnie Mae marketplace is not news, but the stresses now visible on many nonbanks are becoming acute.

Stan Middleman, founder and CEO of Freedom Mortgage, told the IMN conference that nonbanks have had a relatively easy environment over the past few years because of rising home prices, but in a falling home price environment default servicing becomes “very expensive.”

He also noted that when prepayment speeds fall, the float available to nonbank lenders declines, creating challenges for those who have not lived through a rising rate environment. Rising rates and falling home prices are yet another downside risk for the mortgage industry in 2017.

#div-oas-ad-article1, #div-oas-ad-article2, #div-oas-ad-article3 {display: none;}

When it comes to liquidity, the issue facing nonbanks is not simply with respect to funding new loans, but also in supporting loss mitigation and financing MSRs. A perusal of the delinquency data from Ginnie Mae for the top 50 seller/servicers in that market illustrates the potential problem that awaits the industry in the event that residential loan default rates start to rise significantly.

The basic conflict that Ginnie Mae faces is to ensure that the seller/servicers make timely bond payments, but turning a blind eye to accumulating defaults. For nonbanks, coming up with the cash to aggressively resolve delinquencies can mean making a choice between funding loss mitigation and new loan originations. And ultimately the FHA and the taxpayer pick up the tab.

As Matt Maurer of MountainView Capital noted on the same MSR panel with Middleman, Ginnie Mae assets really should be held by commercial banks due to the cash flow requirements. Yet the trend in the Ginnie Mae space is just the opposite, with nonbanks now the largest group in that market and growing.

Bill Dallas of Skyline Home Loans tells HW that Ginnie Mae cash flows are currently negative and getting worse because of how the financing of the servicing asset is used to compensate for the high cost of originations. “I am nervous as a long tail cat in a room full of grandmothers and rocking chairs,” notes Dallas, who is one of the most experienced operators in the business.

The nonbank mortgage sector got some very good news when Ocwen Financial finally settled its dispute with New York, including agreeing on a process to end the onerous monitoring of that firm’s servicing operations. Down the road, Ocwen may actually be able to resume purchases of MSRs and other assets.

Following a series of large MSR purchases by Nationstar earlier this year, it goes without saying that the industry badly needs additional dry powder in terms of servicing capacity in the event of a large nonbank failure.

Many other nonbank servicers are exiting the market because of a chronic lack of liquidity and basic profitability, especially those operating in the Ginnie Mae market. Few of the nonbanks operating in the residential mortgage market actually generate enough profit to cover their cost of capital, notes Moody’s, one reason that the likes of PHH, Prospect and other smaller players have closed their doors.

Many other nonbank servicers are exiting the market because of a chronic lack of liquidity and basic profitability, especially those operating in the Ginnie Mae market. Few of the nonbanks operating in the residential mortgage market actually generate enough profit to cover their cost of capital, notes Moody’s, one reason that the likes of PHH, Prospect and other smaller players have closed their doors.

As Ben Lane wrote for HW regarding PHH, “in just the last year, the company has seen seismic shifts in its mortgage business, with partners like Bank of America and HSBC pulling massive mortgage servicing rights portfolios away from the company.”

One large servicer, Walter Investment Management Corp., has been rumored to be facing bankruptcy after several setbacks. In March, S&P downgraded Walter’s long-term issuer credit rating to “CCC” from “B” with a negative outlook. S&P’s outlook reflects Walter’s “ongoing financial weakness and recently announced deficiencies in internal controls.”

Walter has sold MSRs to raise cash and has tried to transition to a sub-servicer model, but it is questionable whether these changes have actually enhanced profitability on an ongoing basis. At least one Sell Side analyst has predicted that the company will be restructured.

As this writer noted in a working paper on MSRs, “Assessing Involuntary Termination Risk on Residential Mortgage Servicing Rights,” the changes made by Ginnie Mae to their acknowledgement agreement were intended to alleviate some of the liquidity issues facing nonbank servicers.

In the first quarter of 2017, asset-backed securities transactions using Ginnie Mae MSRs as collateral have been completed by PennyMac Mortgage Investment Trust and Freedom Mortgage. These ground-breaking transactions hold enormous promise by diversifying the sources of funding for nonbanks and also increasing the effective advance rate on Ginnie Mae MSRs and loans.

That said, however, the fact remains that nonbanks have limited balance sheet resources and few real capital assets other than the MSR, one reason why federal bank regulators in the U.S. have imposed a limit of 10% of tangible capital on bank MSR holdings, after which the bank must raise additional capital to offset the asset.

This policy stems from the fact that Countrywide Financial had an MSR which at the time had a book value of $18 billion on a balance sheet of $200 billion in assets, meaning that virtually the bank’s entire capital position was essentially represented by the mortgage servicing asset.

Today, a growing proportion of MSRs are supported by nonbanks and smaller, specialized depositories that have great difficulty financing these assets. Many of the more sophisticated players have opted to sell the MSR and become a sub-servicer, preferring to earn the 8-10bp of servicing income without needing to finance the excess servicing. As the interest rate environment changes, notes Freedom’s Middleman, “a lot of people who have been aggregators will be challenged.”

Agreeing with Moody’s prediction about industry consolidation, Middleman predicts that there will be a lot of M&A activity in the mortgage space for the duration of 2017 and beyond.

But more importantly, he warns that in a falling home price market, managing counterparty risk will become paramount. “Whole loan sales carry risks,” he noted. “but co-issuance business will be stressed in a declining home market.”