Across America, millions of households are struggling to find a place to rent they can afford. Fewer than half will find affordable rental housing; fewer than one in four of our poorest renter households will do so. And even those who find a rental will likely face rent hikes in the near future that may eat up any increases in their income. This crisis threatens household stability, education, health, the environment, and the quality of our neighborhoods.

The cost of the crisis is very real to me. In the 1960s, my father lost his job. He got sick at the factory where he worked and he was not part of a union – our home was foreclosed on. We moved around a bit before we settled into public housing in South Philadelphia.

We were lucky. Our rental home was affordable; it was a safety net for us. But I saw so many others struggling to find jobs with decent wages, good schools for their children, and safe neighborhoods. All while grappling with the lack of stable, affordable housing.

At Fannie Mae, we provide affordable housing opportunities for renters and owners. It’s what we focus on every day. This focus gives us some insight into the causes and potential solutions to the current affordable rental crisis.

To help spark creative solutions, we must better understand the scope of the affordability problem, how we got here, and what some communities are doing to address the issues.

What it means to be cost burdened

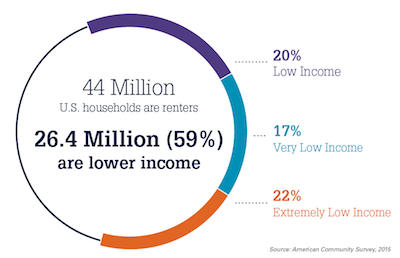

More than one-third of U.S. households – about 44 million – are renters, and nearly 60% are classified as low income (households with income from 51% to 80% of the area median income or AMI), very low income (31% to 50% of the AMI), or extremely low income (below 30% of the AMI). These are the families most likely burdened by rent costs.

Households that spend more than 30% of their income on rent are considered “cost burdened.” While about half of all renter households are cost burdened, an estimated three-quarters of extremely low-income renters are in that category.

Households spending more than half their income on rent are considered to be “severely cost burdened.” About one quarter of all renter households fall in that category, yet that percentage soars to 59% of extremely low-income renters.

For every affordable unit added, two are lost

That’s because there’s a disconnect between the units being built (the supply) and who’s able to rent them (the demand).

While it costs about as much to build an apartment project for low-income tenants as a market-rate project, many builders are focused on projects that will command higher rents. According to the Dodge Data & Analytics Construction Pipeline, about 343,000 apartment units were completed in 2016, with another 400,000 units expected to come online in 2017. Most of this new supply is high-income rentals located in large cities where Millennials are driving rental demand.

When it comes to new affordable units, about 100,000 are built each year on average, says the National Housing Trust. Yet the market supply is not going to keep up: For every new affordable unit added, two are lost from deterioration, abandonment, or conversion to market-rate housing.

Further, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, about 360,000 privately owned, federally subsidized units have been converted to market-rate housing since 1995, with another 10,000 to 15,000 units leaving this inventory every year. In addition, more than 2 million units are at risk of loss over the next decade.

How did supply dry up?

During the Great Recession, multifamily construction fell sharply. After the recession ended in June 2009, demand started to rise – both from previously displaced renters and from new Millennial first-time renters. However, multifamily construction didn’t rebound in a significant way until 2013, and has been playing “catch up” ever since.

In addition, construction of subsidized housing has declined as a percentage of all new multifamily construction and now represents only around a fifth of new construction annually – not enough to keep pace with demand.

Finally, costs of construction, including rising wages for construction workers nationally, have increased across the country, not just in strong metropolitan areas.

As a result, without a subsidy, developers are only willing to undertake new projects where they can generate higher rents.

Driving demand

Increased demand for rental housing stems from several factors. Millennials, those 75 million young adults born after 1980, are one of the biggest drivers of current rental housing demand. In record numbers, they are deferring homeownership, choosing to rent rather than buy. High-income renters, typically those who can afford to buy a house, are choosing to rent an apartment instead. They now represent more than 20% of all renter households. Collectively, this contributes to a 26% increase in estimated national rent levels since 2005.

Wage growth is starting to line up with rent increases

Wages and asking rent levels are two factors that play a big role in affordability. All other things being equal, it’s more affordable to rent when wage growth keeps pace or stays ahead of rent increases.

It looks like that’s starting to happen. Over the next two years, growth in household income is likely to outpace growth in asking rents by about 2%, cumulatively. But that’s based on projections showing that median household income might grow by nearly 7% while rent growth returns to more normalized levels in the 2 to 2.5% range.

Even so, this will contribute to only modest improvements in rental housing affordability.

What's the answer? Click here to find out how communities are working toward solutions in Part 2.