The Congressional Budget Office released a report Thursday exploring four proposed solutions for lessening the cost and risk of the reverse mortgage program to the federal government.

Reverse mortgages are insured by the Federal Housing Administration, which upholds a guarantee that requires it to make up for the shortfall should a loan default or the property value exceed the loan amount.

But in recent years, the reverse mortgage program has been a drain on FHA’s flagship Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund. In November, FHA’s annual Report to Congress revealed that the HECM program bled the MMI Fund for the third consecutive year, causing a deficit to the tune of nearly $14 billion.

In its report, the CBO projects that the FHA will guarantee 39,000 HECMs in 2020, which is 8% more than the 2019 forecast but 20% less than 2018’s – a decline it attributes to 2017 program changes that have borrowers looking at other means of extracting equity.

But while the report estimates that under one type of budgetary analysis, 2020’s newly originated loans would “produce a small budgetary savings over their lifetime” for the government, it acknowledges that the program continues to face scrutiny from lawmakers concerned about the risks to FHA and borrowers and the cost of those risks for the government.

The CBO goes on to outline four possible solutions to easing the cost concerns of the program, all of them drastic, none of them good – for lenders or for borrowers.

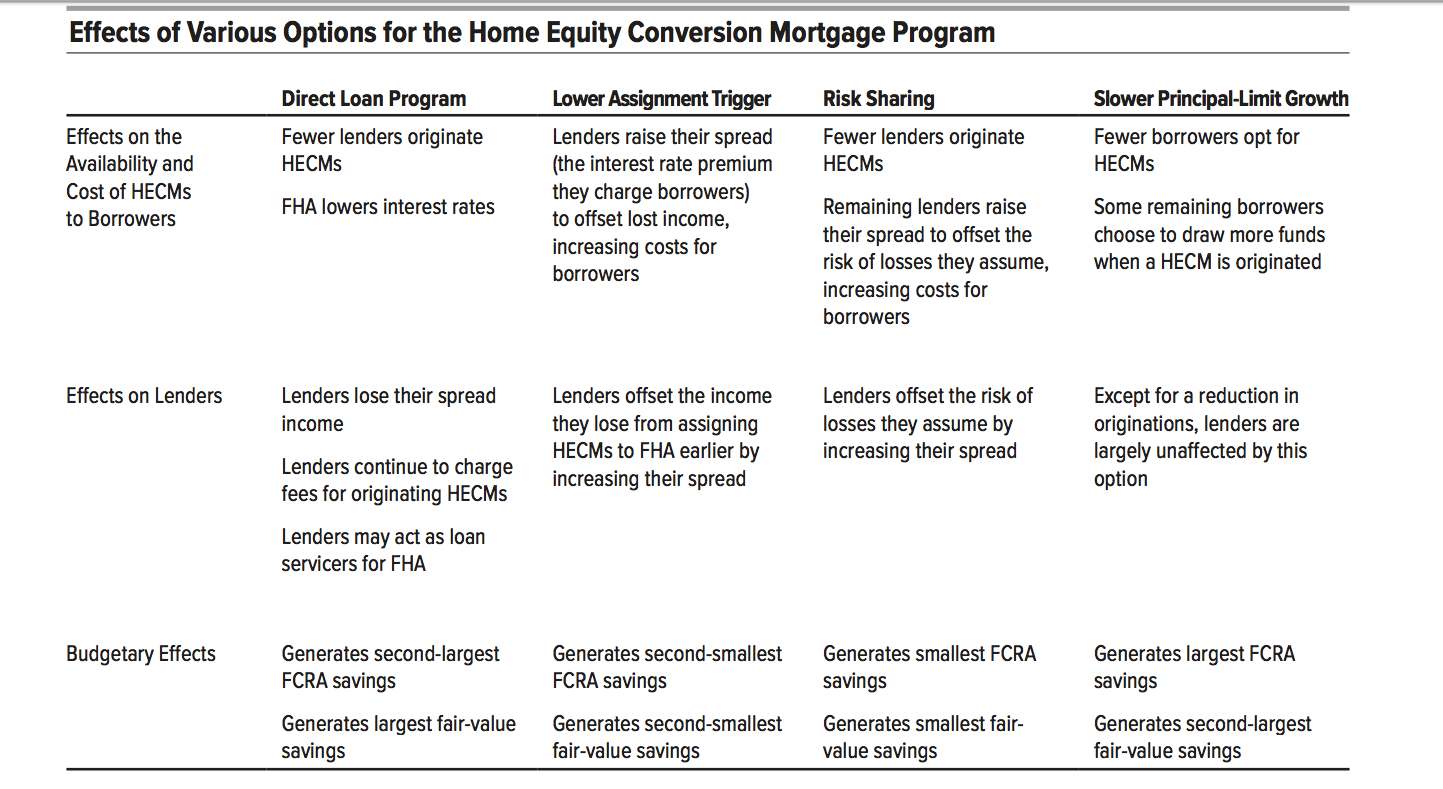

The report explores the potential impact of each proposed solution, including the impact on budget, on lenders and on the availability and cost of the program to borrowers, but it does not offer any recommendations.

Here is a recap of the proposed solutions and their potential impact:

1. Making the HECM a direct loan program

In this scenario, the government would fund reverse mortgages rather than guarantee loans funded by lenders. Lenders would still contact borrowers and take applications, but the FHA would make loan disbursements directly to borrowers and service the loans itself.

The CBO says this option could allow for savings by allowing the FHA to achieve an economy of scale in non-financing costs that are not available to lenders, and it could also use the economy of scale to reap savings on the monitoring and servicing of loans.

But the analysts did acknowledge some drawbacks: “On the basis of feedback from market participants, CBO estimates that if FHA was solely responsible for maintaining and selling foreclosed properties, it would not be able to manage the scale of those dispositions as effectively as when it shared that responsibility with lenders.”

This might also cause lenders to raise their fees to make up for lost spread income, and it could convince some to leave the business altogether, the report noted.

While the report says the impact on borrowers would vary depending on the specifics of the FHA’s implementation, there is sizable potential for problems if the government were to assume a larger role in the market.

“If a larger government role in the HECM market led to greater inefficiencies and less innovation over the long term, taxpayers could suffer and borrowers could miss an opportunity to tap into their home equity,” the report states.

2. Lowering the assignment trigger

Currently, lenders assign a HECM to the FHA when the loan’s outstanding balance reaches 98% of the maximum claim amount, or MCA. But in this scenario, the FHA would reduce the assignment threshold to 80% of the MCA and make assignments mandatory at that point.

This would allow the FHA to earn more spread income on loans, but the savings could be offset by higher costs if the agency was unable to manage the increased number of foreclosures it would have to deal with if loans were assigned earlier.

As for lenders, they would stop earning interest on loans once they were assigned, and this could cause some to flee the business. This would also likely reduce the number of HECM originations by 5% as lenders would probably be forced to raise borrower costs to recoup losses.

3. Sharing more of the risk with lenders

In this scenario, the lenders would be required to hold on to an active loan longer than they currently do before assigning it to the FHA. In effect, this would have the FHA only guaranteeing a portion of the losses, forcing lenders to cover the rest.

But this option could come with some weighty consequences, the report acknowledges.

“That change could make HECMs less available because lenders might be unwilling to accept their share of the risk on certain borrowers, or they might charge borrowers a higher interest rate or higher fees to recoup the fair-value cost associated with the risk of losses they were being asked to bear,” the report notes.

If the FHA were to reduce insurance premiums to offset borrower costs, this could detract from the savings the government would incur from making such a move.

The one major bonus of this move, according the report? More encouragement for lenders to grow the proprietary reverse mortgage market.

4. Slowing the principal-limit growth

Under current rules, a borrower can establish a HECM line of credit that grows over time – one of the loan’s most compelling features and a major selling point for using the HECM in retirement income planning.

But this scenario would put an end to that strategy, effectively reducing line-of-credit growth “by just enough to keep the amount of a borrower’s undrawn funds steady.”

“Slower growth of the principal limit would reduce budgetary costs to FHA by decreasing the likelihood that a loan would terminate with a balance greater than the home’s current value,” the report explains.

The main impact of this scenario is that more borrowers would increase their initial draw and forgo establishing a line of credit, and originations would likely decline by about 5%, the CBO projects.

Here is a chart by the CBO that breaks down the potential impact of each option (click to enlarge):

This report was conducted at the request of the House Committee of Financial Services, and in keeping with the prerogative of the CBO, it declines to draw any conclusions from its analysis, offering only what it calls an “objective, impartial analysis.”

The reverse mortgage industry will no doubt have some very apt, subjective and partial reactions to the solutions proposed above – stay tuned.