While the nation is consumed with the impacts of the coronavirus and the safety of friends and family, as well as the economic impact on our communities and businesses, the housing finance sector needs to begin thinking about ways housing can help lead the nation back to improved productivity and growth.

The real estate industry—and all the ancillary benefits it creates with new jobs, goods and services—accounts for roughly 40 basis points of the country’s GDP. Restoring a healthy real estate market will have a significant positive impact on our economy.

Before the impact of the pandemic became clear, we were all looking forward to a robust year and a strong spring market fueled by a migration of Millennials from rental into homeownership and aided by near-historic low interest rates and full employment. In fact, the only concern was the shortage of available inventory to serve this market.

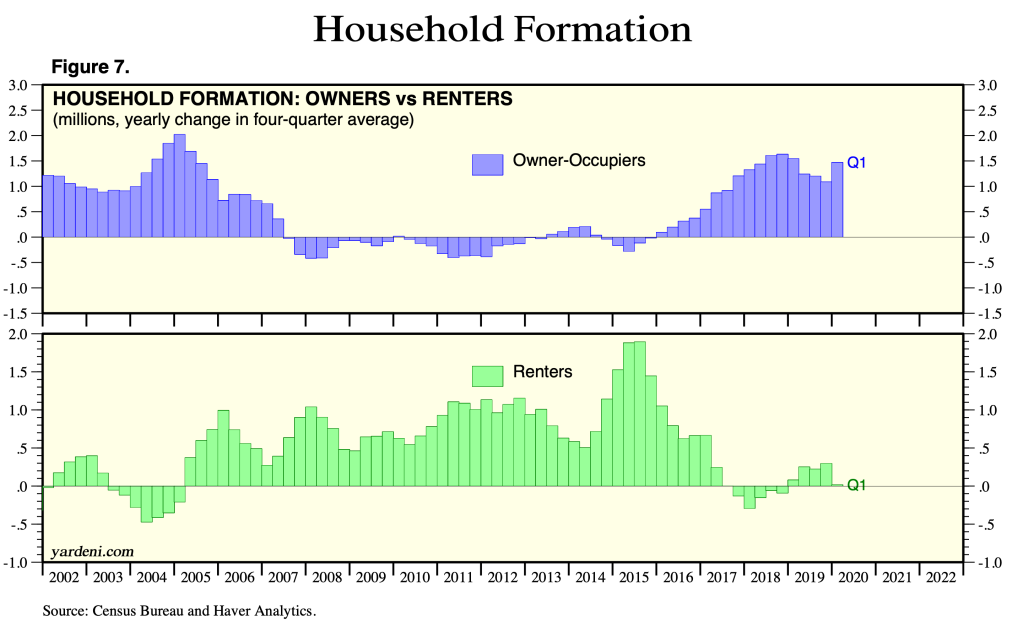

This is all due to demographics, as demonstrated by the chart showing household formation. In 2008, when the Great Recession began, not only was America facing excessive credit risk and unsustainable loan products, we were actually losing owner-occupied households, with the only growth being in rental housing. Fast forward to the last few years and the opposite is true—owner occupied household growth is well over 1 million per year and rental household formation is declining. What happened?

For one thing, Millennials are a decade older, no longer home from college and living in their parents’ basements, but part of the workforce and establishing their own homes. A decade ago, my household had six occupants and today my family makes five different households.

This trend is driving the demand that will fuel the housing economy for many years to come.

The chart on household formation by Yardeni Research shows the growth in household formations among owners versus renters.

But the impact of what we’re facing now, as well as other demographic conditions, may pose challenges to those who otherwise want to own. The Urban Institute in its 2018 paper, “Barriers to Accessing Homeownership Down Payment, Credit, and Affordability,” pointed to down payment, credit availability and affordability as the three key factors limiting access.

The impediment of a down payment will only be exacerbated by the economic impacts of COVID-19, after otherwise creditworthy borrowers have been forced to tap into their savings due to job furloughs or losses, pushing the American dream of buying their first home even further out of reach.

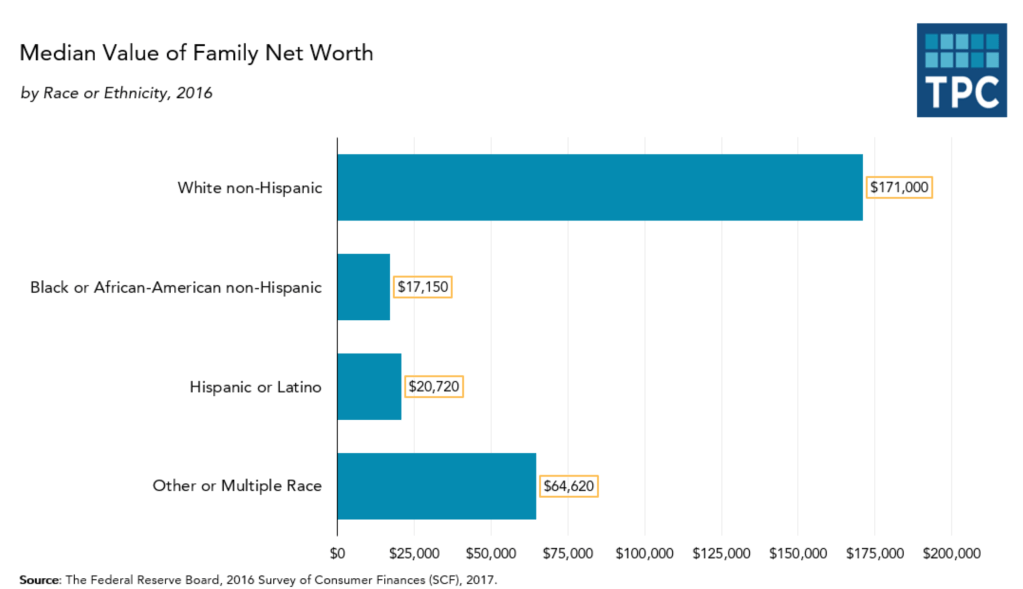

For policymakers, this poses a real problem. If you look at existing U.S. housing stock, approximately 70% of all homes are owned by white, non-Hispanics. But, if you look at what makes up the demographics of future household formation, we see a dramatically different picture. Roughly two-thirds of all new households will be formed by minorities, primarily African-American, Hispanic and Asian.

This creates challenges because minorities generally do not have the benefit of inherited wealth to aid them in buying a home, unlike their white counterparts. In fact, on average, the wealth of whites is significantly higher than that of minorities.

According to the Federal Reserve Board, the median net worth of whites is almost 10 times higher than African-American families and eight times higher than Hispanic families.

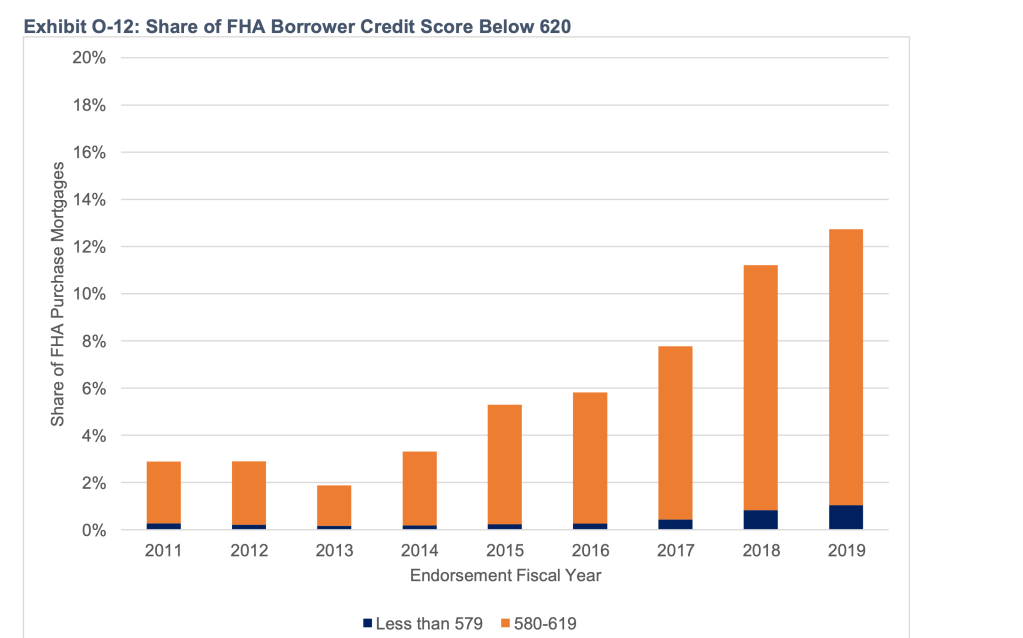

For policymakers, this demands a new way of thinking. It is already becoming clear what is needed to help support access to this new demographic of people who cannot count on mom and dad to help with the down payment. And that clarity was shown by FHA’s annual report to Congress in 2019. Roughly 40% of all FHA purchase transactions had some form of down payment assistance.

For FHA, DPA loans have always posed a greater concern than mortgages with the traditional required down payment. And there have always been several types of down payment assistance. A down payment could be provided by a parent or relative, an employer, various housing finance agencies that used to be able to raise those proceeds by issuing mortgage revenue bonds or even secondary market revenue—a scenario that has created a swirl of debate these past few years.

As a former FHA Commissioner, I share the view of former commissioners that we can never repeat the horrendous lesson learned from the infamous Seller Funded Down Payment Assistance, frustrating then-Commissioner Brian Montgomery in his role as FHA chair during President George W. Bush’s administration. SFDPA was eliminated by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, but the wave of defaults fell in my lap that first year with the program producing the defaults of roughly one in three FHA-insured mortgages.

To be clear, this was not just about mortgage defaults, this was about the disruption to families and destruction to credit ratings of thousands of people—mostly minorities—because of this one program. You see, in order for the seller to fund the down payment, they simply raised the home price high enough to cover it, and when the family moved in they were already under water, and this was only magnified by declining home values that followed during the Great Recession.

I am concerned that other options for down payment assistance—with the exception of those provided from secondary market revenue—do very little to help minority homeownership, or access to homeownership for anyone without a mom and dad with extra cash. The traditional role that housing finance agencies played in issuing mortgage revenue bonds to raise money for down payments just does not work in today’s marketplace. It’s literally an illiquid market.

Diving into down payment assistance

So, I began looking into down payment assistance created from secondary market revenue as potentially the best option for providing the down payment needed to buy a home. What I found is that most DPA loans have secondary market revenue as part of the program.

Using this approach to DPA has endured scrutiny over recent years. Regardless, if we are to look at a program to change the homeownership rates for those not born into a family with intergenerational wealth, we need to think differently. As HMDA data shows, black homeownership is as low as it was when housing discrimination was legal decades ago. After decades of attempts by presidents from both sides of the aisle attempting to change the paradigm, we have made zero progress.

Something has to change.

The question is whether we can stand up a sustainable DPA program that will eliminate the need for inherited wealth to make the down payment. In my search, I looked for ways in which to make a DPA product funded by secondary market revenue actually work, adhering to some of the following principles: integrating financial literacy education and coaching for borrowers, requiring borrower reserves, creating incentives that lead to greater commitment from borrowers, and instituting more controls on underwriting. If we can solve the down-payment problem in a manner that does not increase default risk, we may have one solution to support the kind of paradigm shift needed. One important thing about secondary market revenue as a source of funding is that, unlike SFDPA, it does not produce an artificially inflated home price. It does not produce immediate negative equity any more than any other HUD program. It simply helps a borrower get into a home without needing to spend years more than others to save up for the down payment.

In my search, I found, and began a deep dive into, one program in particular that seemed to check many of these boxes—a program offered by CBC Mortgage Agency through its Chenoa Fund. CBCMA, based in Utah, developed a DPA program that, while using secondary market revenue, maintains a variety of protections to ensure borrower success. These protections could become a model for HUD to consider should they propose a way to manage this form of DPA. Here are just a few examples of how CBCMA is leading in this area:

1. CBCMA contracted with Hope Loan Port, an organization whose board I was a member of while president and CEO of the Mortgage Bankers Association. HLP helped by being the conduit for mandatory pre-purchase home buying counseling for borrowers with credit scores below 640, and working to raise that to 670, who desired to get a loan. Since the partnership, CBCMA and HLP met monthly to review results and discuss solutions such as developing a feedback loop for at-risk borrowers. Most importantly, CBCMA absorbs all the cost for the counseling, which is now performed by Money Management International.

2. CBCMA also provides a free post-purchase counseling program called the “Borrower Success Program.” All borrowers are automatically enrolled in this program and it keeps the housing counselors in close touch with the borrower for a full year following settlement. They are also looking to extend this for 24 months given the demand and what they perceive to be its value, particularly as recent and new borrowers are facing the impacts of the pandemic.

3. At CBCMA, the down payment assistance is always structured as a second mortgage. This helps to improve borrower commitment. It comes in three forms, but an example of one provides forgiveness of the second mortgage after three years of timely payments on the borrower’s first—setting a major incentive for the homeowner. And during this three-year period, the second mortgage is “silent,” meaning the borrower only needs to make payments on their FHA-insured mortgage. This gives the borrower instant “skin in the game” and incentivizes them to stay current on their mortgage from the start.

4. CBCMA also sets a 620 floor for all DPA loans, but that can change and typically varies between 620 and 640 based on factors such as a borrower’s history making payments like the one being considered, and other measures that reflect a demonstrated ability to support their liabilities such as a maximum 125% payment shock.

5. CBCMA caps back-end DTIs, too. For example, if your FICO is between 620 and 639 the DTI is capped at 31% for housing and 45% for the secondary ratio.

6. CBCMA has reserve requirements for borrowers that vary by credit quality but can include factors like meeting the VA residual income test, at least two years employment with the same employer, or two months PITI reserves, among others.

7. CBCMA does a full second credit review of each FHA mortgage to ensure that it meets all FHA guidelines.

How does a program like this help? First, 54.3% of all borrowers assisted through the Chenoa Fund program in 2019 were minorities. Even more importantly, 34.8% were the first generation in their family to ever own a home. The point is this—by deploying risk management that is multilayered, consistently reviewed and evaluated, and includes a thorough due diligence on every loan to check for fraud, appraisal quality, and other eligibility criteria, this program can be the foundation of a game-changing model to support real change in homeownership statistics in the years ahead.

I have been an outspoken voice raising concerns about DPA programs, but the frustration that we all face is in answering the question of how we affirmatively impact the long-term wealth of those who did not inherit it. How do we create stability and lifestyle support for families not wanting to relocate every time a lease expires? Funding these programs through secondary market revenue is a solution that creates no greater homebuyer risk than another DPA mortgage and may even perform better given the more conservative underwriting. What is unique about Chenoa is that they operate nationally. This helps keep the state HFAs more competitive as they eliminate any monopoly advantage, and this can only produce better rates and better customer service—something that competition provides.

In the end, this only solves one of the three problems of advancing access to homeownership—the down payment. Credit availability and affordability will come from building more entry level housing and encouraging that to happen through public policy and private partnerships. My research has changed my way of thinking on DPA as a solution. HUD should lead the way by taking a program like CBCMA’s Chenoa Fund and standardizing these types of best practices to ensure sustainability. If we work together on this, we can effect meaningful change that will help families for generations to come.

To read the full June issue of HousingWire Magazine, click here.